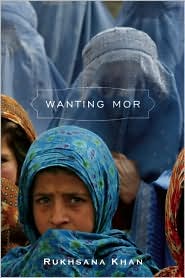

Wanting Mor

Wanting Mor

Written by Rukhsana Khan

Groundwood Books, 2009, 192 pages

ISBN: 978-0-88899-858-3

This book is about the universal themes of the search for identity, self-understanding, and coming of age through the story of a young girl, Jameela, in an Afghani village and in Kabul. The events of the story encapsulate the trajectory of the protagonist’s life from a confused, lost child to a confident young woman. The story is set in 2001, after the U.S. invasion and the influence of Taliban tyranny. Jameela is born with a cleft lip that she hides behind a Porani (head covering). The porani comes through as a metaphor of her identity as a Muslim as well as her protection. Her faith in Islam and her mother’s love sustain her throughout the story. The reader feels the presence of the mother even though she dies as the story opens in a dusty, remote village where food and support are scarce after war on terrorism has taken a severe toll on human and economic life. Mor means Mother in Pushto, one of the dialects spoken in the northwestern region of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The first chapter is heart wrenching in its depiction of a child’s grief as she loses the one constant factor in her life — her mother. Her life has been unstable ever since she was born due to the constantly unpredictable nature of the circumstances surrounding her home land. Her father decides to move to Kabul for a better life the day after her mother dies and sells all that is dear to Jameela, including her mother’s clothes. He loses the money in gambling, drugs, drinking, and debauchery in modern Kabul. They are later kicked out of a household of his “friend” in Kabul when he is caught in a compromising position. He then decides to marry someone he seems to have met while his daughter was working at his friend’s house. Jameela is forced to work as a servant/slave in her own home and every household she goes to but remains determined to do good. She accepts that her face will never be her fortune as people look away as soon as they perceive her deformity. The climax of her unfortunate events is when her father abandons her in the middle of the Bazaar because her stepmother cannot stand her budding understanding and friendship with her son.

The believable character of Jameela is woven as a Muslim girl and a daughter, who is essentially a pious person. Her character is shown in direct contrast to the negative characters of other women and her father. The evil nature of her stepmother and Agha Akram’s (the butcher) wife, who convinces her husband to put Jameela in the orphanage, off-set the pious character of a Muslim girl whose faith holds her together against all odds. The weak personality of her father and his friend in Kabul is scaffolded by the stronger Muslim male characters of her stepbrother and Agha Akram, the kind-hearted butcher who helps her when she is abandoned in front of his shop.

Jameela’s strength is her religious belief that she falls back on in making sense of all that is new to her such as her father’s drinking and irresponsibility. She realizes the difference between right and wrong even as she is surrounded by wickedness. The education that she receives in the orphanage and the actions of the U.S. army seem to be Jameela’s saviors. The influence of the foreigners (U.S. soldiers) is shown negatively through the over modernization in women’s clothing. The blind following of revealing western clothing and behaviors to the extent of drinking alcohol and corruption is shown as a reaction to Taliban departure and subsequent western influence brought in by the U.S. soldiers. The general mistrust of Americans is strongly portrayed but their ability to fix things is also accepted as they arrange to transform Jameela through repairing her upper lip and to help the orphanages get better plumbing and sanitary conditions. The reason behind so many children in the orphanages is down played. The social and the political “disasters” of national import are underplayed in comparison to the personal everyday experiences of the characters in this book.

References to religion are strong and woven into the very fabric of the narrative. Islamic feminism is brought to the fore many times during the story in how men show respect to Jameela when she goes out properly dressed. The choice of how a woman covers herself is depicted as varying from woman to woman with decision making resting on the women, including Jameela when she decides how to spend her future life as a teacher. Unlike other novels set in this region of the world, the child protagonist is shown as accepting the conformity demanded by religious norms and restrictions.

The story and the character development lose momentum after Jameela goes into the orphanage and her struggles are influenced by peer pressure and her intolerance towards a poor little girl, Arwa, who is “dirty.” This character transformation negates the humble and gracious protagonist who, in the beginning of the story, accepts everything and all people she meets. She is nauseated by the girl and does not try to do anything about her response until late in the book. The time frame is also confusing for the events at the beginning of the story. For example, shortly after the death of Mor the narrative unexpectedly states that it has been a month since her death. Jameela changes from a very young child into a woman in a seemingly short time span.

The author has written multiple picture books about Muslims set in regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan. She is a Pakistani, who settled in Canada when she was three. She consulted with her sister-in-law who is from Afghanistan for this book. Several issues of authenticity in this book include her confusion of the clothes of Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) wives with clothes worn by Jameela which were essentially Afghani not Arabian in any way (p. 137). She also uses references to a hadith (sayings of the Prophet) that are confusing (p.146) and talks about the negative aspect of following the foreigners to the point of jumping off of a higher place to certain death. In an interview the author elaborates on the manner in which she became inspired to write this story through narratives that came to her from the orphanages that she sponsors in those regions (see her interview at http://www.semicolonblog.com/?p=7729).

The story touches on authentic aspects of Afghani culture that are representative of the society through the inclusion of negative and positive Muslim characters. Attention is given to the agency of Muslim women and the power of choice and education. This book does not seem to reinforce many common stereotypes of Muslims in the Middle East even though the backdrop is dated. The intended audience in the U.S. and other English-speaking countries are exposed to diversity within the society, which encompasses the middle class and the very poor as well as contrasts between varied characters, who are good and evil. It is authentic in the incorporation of religion in everyday life. The author has fashioned a seamlessly authentic portrayal of men, mothers, and girls which does not negate the religious foundations of their lives.

This novel can be read along with research on ways of life of Afghani people and Islamic religion. Variations of some of the same thematic threads can be found in other novels set in Afghanistan and Pakistan by authors outside and inside of the culture including The Breadwinner Trilogy by Deborah Ellis, Beneath My Mother’s Feet (Amjed Qamar, 2008), Iqbal (Francesco D’Adamo, 2003), and Shabanu: Daughter of the Wind, Haveli, The House of Djinn, and Under the Persimmon Tree, (Suzanne Fisher Staples 1989, 1995, 2008 & 2005).

Several references for research on Muslim women and the veil include:

Ayotte, K.J. & Husain, M.E. (2005) Securing Afghan women: Neocolonialism, epistemic violence, and the rhetoric of the veil. National Women’s Studies Association Journal, 17(3), 112-33.

El Guindi, F. (1999). Veil: Modesty, privacy and resistance. Oxford: Berg.

Hirschkind, C. & Mahmood, S. (2002). Feminism, the Taliban, and politics of counter-insurgency. Anthropological Quarterly, 75(2), 339-54.

Hoodfar, H. (2003). More than clothing: Veiling as an adaptive strategy, in The Muslim veil in North America: Issues and Debates. (Eds.) S.S. Alvi, H. Hoodfar, & S. McDonough (pp. 3-40). Toronto: Women’s Press.

Hurd, E.S. (2003). Appropriating Islam: The Islamic Other in the consolidation of western modernity. Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, 12(1), 25-41.

Whitlock, G. (2005). The skin of the burqa: Recent life narratives from Afghanistan. Biography, 28(1), 54-76.

Seemi Aziz, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK

WOW Review, Volume II, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/ii-2/

I really enjoyed reading this book. It shows viewers what its like to live in India during the struggle of WWII. It also shows some of the hardships women faced during this time. While reading this I felt very close to Vidya. I would reccomend this book to anyone especially young teens who are trying to find themselves.