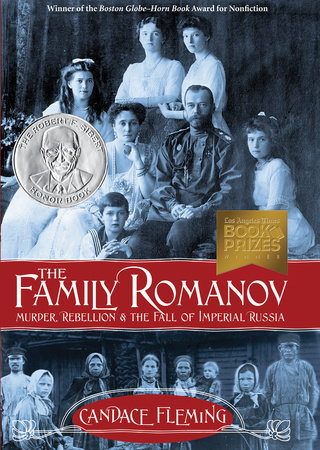

The Family Romanov

The Family Romanov

Written by Candace Fleming

Schwartz & Wade, 2014, 292 pp.

ISBN 978-0-375-86782-8

By combining an intimate family portrayal with intrigue and politics, this compelling narrative captures the imagination and intellect of readers. Fleming tells the familiar story of the doomed Romanov family within the context of social unrest and turmoil in Russia during the early 1900s. She invites us into the lives of Tsar Nicholas, his wife Alexandra, and their five children, providing intimate details about each family member and their closeness and isolation as a family. Their lives of extravagance and wealth stand in sharp contrast to the desperate poverty of the common people, which Fleming reveals through interspersing stories of the Romanovs with firsthand accounts from workers and peasants. Nicholas refused to acknowledge or act to change those social conditions, except to violently repress occasional uprisings. Years of deprivation and oppression and the high cost of World War I created conditions that fed resistance and uprisings. At the same time, Alexandra and Nicholas were distracted by their young son’s illness and turned to a self-proclaimed holy man Rasputin, causing further alienation and rumor. Rasputin and Lenin played key roles in using the German invasion of Russia to manipulate both the weak tsar and disillusioned citizens into a revolution. Fleming’s ability to craft an exciting narrative of intriguing individuals within a complicated history of desperation and oppression results in a powerful work of nonfiction that received multiple awards including:

• The Boston Globe-Horn Book Award for Nonfiction

• Robert F. Sibert Honor Book

• ALSA Excellence in Nonfiction Award Finalist

• Winner of the Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction

Fleming makes excellent use of a wide range of primary sources, including ones that became available after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. By integrating excerpts from diaries, letters, memoirs, and other firsthand accounts along with photographs, she brings multiple voices and points of view into the narrative, vividly portraying the details of people’s lives. She weaves the voices of the Romanovs with the voices of peasants and factory workers, providing a strong contrast that traces the deplorable conditions and increasing tensions that led to the Russian Revolution and the deaths of the Romanov family.

The meticulous research that underlies this book is evident through the many excerpts from primary sources and the captioned photographs, as well as the inclusion of source notes and a lengthy bibliography along with a map and genealogy. Fleming describes her initial interest in uncovering the true story of what happened to Russia’s last imperial family and her growing questions about how this could have happened that led her to take a wider lens. She notes that the book is three stories in one—an intimate look at the Romanov family, the sweep of revolution from the worker’s strikes of 1905 to Lenin’s rise to power in November 1917, and the personal stories of the men and women who struggled for a better life (p. 256). She includes an extensive bibliography and indicates that she talked with Russian scholars, examined thousands of photographs and dozens of newspapers, and read Karl Marx. She worked with archivists at two key collections to get access to original sources and traveled to Russia, retracing the footsteps of the Romanovs. She was able to get access to previously unavailable primary documents in museums and archives due to the collapse of the Soviet Union and discusses the differing translations of these documents and how she selected which to use. This careful description and documentation of her research process and decisions not only are essential to establishing the credibility of her work but also provide readers with insights into the inquiry processes that they can engage in themselves to look at history.

This book can be paired with other books set in the Soviet Union era, such as M. T. Anderson’s (2017) Symphony for the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad, set during WWII, 1941-1944, or with Eugene Yelchin’s Arcady’s Goal (2015) and Breaking Stalin’s Nose (2011), both set in the 1940s and 50s during the time of Stalin. Another interesting pairing would be to pair historical fiction about the Romanov family with this nonfiction book to critically examine the ways in which the authors have played with historical facts in their narratives. Possible pairings include The Lost Crown (Sarah Miller, 2012), Tsarina (Patrick Nelle, 2014), Anastasia’s Secret (Susanne Dunlap, 2011), and Anastasia and Her Sisters (Carolyn Meyer, 2015).

This book is both a biography and an introduction to this time period in Russian history. It is also a great read that brings history to life. The Family Romanov is proof that history does not need to be boring and dull, but instead as riveting and absorbing as any novel.

Kathy G. Short, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

WOW Review, Volume X, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at http://wowlit.org/volume-x-issue-2/.