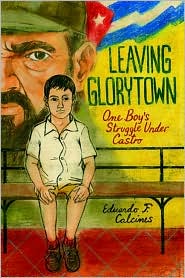

Leaving Glorytown: One Boy’s Struggle under Castro

Written by Eduardo F. Calcines

Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2009, 221 pp.

ISBN: 978-0-374-34394-1

In this memoir, Eduardo Calcines shares how, as a child, he had to deal with the harsh realities of daily life in Communist Cuba. In January 1959 when Fidel Castro comes to power, Eduardo is a three year-old living on San Carlos Street in the barrio of Glorytown in the city of Cienfuegos. He has the special love of his Abuelo Julian and Abuela Ana who spoil him and protect the boy when his mother gets angry. Aunts, uncles, and neighbors congregate around the Calcines home. Eduardo has countless cousins and friends with whom to play. Holidays like Noche Buena at Christmastime are feasts of food, dancing, and laughter. But on that holiday in 1961, a gang of henchmen invade the party and call the family members “worms,” traitors to Castro’s cause; the ensuing brawl signals the end of an era. Shortly after, Cubans are no longer allowed public meetings.

Eduardo becomes more and more aware of the hardships his family faces under Castro’s government. Food is rationed; his mother stands in long lines for dry bread, tins of Russian horsemeat, and a bit of sugar. Eduardo’s father, Felo, is not a Communist and speaks out loudly against the regime. The Calcines begin to talk of emigrating. To do so they must leave behind their beloved family and friends and never return to their home country. They will also suffer persecution by the government until their exit visa is granted. Eduardo is seriously harassed and humiliated by his teachers and classmates. Felo is sent to a prison camp where he works the fields 14 or 15 hours a day.

This discrimination and suffering is counterbalanced by Eduardo’s dreams and his family’s stories. Eduardo imagines that in the land of blond people, the United States, there are giant hams, nice neighborhoods, a place where his father will have a good job and where kids never get into fights. Abuela Ana and Eduardo’s father Felo tell funny and tender stories that ease the pain of the family’s suffering. One of Abuela’s often repeated stories is about how she once spared an intruder the loss of his fingers by intentionally striking the floor with her machete rather than cutting his hands. Felo’s best stories are about his own difficult childhood; he dropped out of school in the third grade when his father died and went to work. Felo also tells sweet stories like the one about his courtship of Eduardo’s mother. All of these stories within the story communicate values and messages of compassion and hard work, and the importance of God, family, and country.

Calcines’ memoir draws to a close when the long-awaited telegram arrives, giving the family permission to leave the country. Fortunately, this happens just before Eduardo’s fifteenth birthday when he would have been drafted into the Cuban army. The wrenching parting scenes and a heart-stopping moment when an official claims there are no seats for them on the airplane will engender empathy in readers. Some will come to understand the conflicting emotions of many immigrants, some of whom would rather stay in their home countries if they had a choice. The author’s descriptions of neighborhood happenings are rich with culturally-specific details that paint a colorful portrait of this close-knit neighborhood. Readers will remember the unique characters of Glorytown and the high hopes Eduardo and his family have for their new life.

Leaving Glorytown: One Boy’s Struggle under Castro raises issues of social class and forms of government. Readers learn little about what life was like for the Calcines and Espinosa families before Castro ascended to power. Conducting an investigation into previous Cuban leaders, such as dictator Batista, may invite readers’ questions about why Cuba has been vulnerable to dictatorships. Educators can guide readers as they ask critical questions about access to power, justice and human rights for average citizens in Cuba and beyond. In the epilogue, Calcines tells about his life after his family’s arrival in the U.S. Like many ex-patriot Cubans, he longs to return to his home country, to walk in his old neighborhood and see his long-lost friends. Students may ask why the author cannot visit the island of his childhood and want to learn more about Cuban/U.S. relations. Questions such as these may spark an inquiry that could be supported by current newspaper articles.

This memoir can be paired with other coming-of-age memoirs that are shaped by the politics of the times such as Zlata’s Diary: A Child’s Life in Sarajevo by Zlata Filipovic (1994), They Poured Fire On Us from the Sky: The True Story of Three Lost Boys from Sudan by Benson Deng, Alephonsion Deng, and Benjamin Ajak, with Judy Bernstein (2005), Revolution is Not a Dinner Party by Ying Chang Compestine (2007), and Stealing Buddha’s Dinner: A Memoir by Bich Minh Nguyen (2007).

Judi Moreillon, Texas Woman’s University, Denton, TX

WOW Review, Volume I, Issue 4 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/i-4/

2 thoughts on “WOW Review Volume I Issue 4”

Comments are closed.