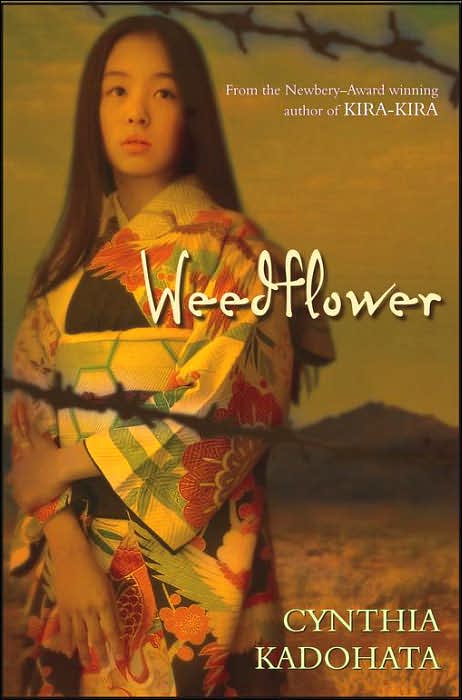

Weedflower

Written by Cynthia Kadohata

Atheneum, 2006, 257 pp.

ISBN: 978-0-689-86574-9

“As they walked more and more people joined them. About a thousand Nikkei waited with their possessions at the gate. Hundreds of others had gathered to watch them leave.” (p. 96)

A historical novel, Weedflower presents the story of Sumiko, a 12-year-old Japanese American girl, whose family is relocated to an internment camp during World War II. The family must leave their thriving flower business and their home in California to go to an internment camp in Poston, Arizona, with no chance to regain their life and livelihood. As the story unfolds, Sumiko is confronted with the humiliation of being ostracized by her classmates, the necessity of destroying family heirlooms that might mark her family as unpatriotic, and the ironic twist of having her brothers serve in the U.S. armed services even as the family is restricted to a camp. An additional element of this text involves the location of the internment camp itself – on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. The stark contrast of moving from California to Arizona is highlighted as is the tenuous relationship between the Japanese Americans and the Mohave people. Sumiko’s budding friendship with Frank, an astute Mohave teenager, is enlightening for both of them as they learn how to negotiate the challenges they face in respect to prejudice and stereotyping. Based on historical events, this story highlights how people learn from one another, and how their seemingly disparate circumstances may intertwine and benefit each other.

With a disquieting sense of inhumanity and compassion, Weedflower is a middle grade novel that leaves readers questioning the reasons for internment camps and the ways in which people are treated as a government attempts to balance its own fear and issues of safety. Sumiko and Frank are extraordinary characters who support readers in making connections to the biases found throughout history as well as in evaluating the changes or lack thereof that have occurred as a result of such circumstances in the past. A novel about the inevitability of change, the power of family, and the possibilities that exist when we are willing to explore the opportunities that come with change, Weedflower is an engaging novel that could be a vital part of identity literature for young people.

There are several ways to utilize this text. It could be part of a unit on what was happening in the United States during World War II along with The Summer of My German Soldier (Bette Greene, 1993), Farewell to Manzanar (James Houston & Jeanne W. Houston, 1983), Journey to Topaz (Yoshiko Uchida, 2004), Remembering Manzanar (Michael Cooper, 2002), and Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family (Yoshiko Uchida, 1984). In respect to a unit about cross cultural convergences between different ethnic groups or geographical locations, Weedflower could be paired with The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (Sherman Alexie, 2007), American Born Chinese (Gene L. Yang, 2006), Dakota Dream (Michael Bennett, 1993), or The Real Plato Jones (Nina Bawden, 1993).

Cynthia Kadohata’s father was held in the Poston internment camp during World War II, and it is his experiences from which she draws her story. Using her father’s stories, as well as documentation of other Japanese Americans’ experiences, Kadohata chronicles the effect of the government’s internment policy during World War II. She also includes a brief historical note at the end of the text to inform readers of what happened to the internment camp at Poston and to the Native Americans and Japanese Americans who joined the military in spite of being alienated by U.S. citizens and U.S. governmental policies.

Holly Johnson, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

WOW Review, Volume I, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/i-2/

2 thoughts on “WOW Review Volume I Issue 2”

Comments are closed.