When a boy anonymously shares his snack with a homeless man, he begins a cycle of good will.

Featured in WOW Review Volume XII, Issue 4

Material appropriate for all ages

When a boy anonymously shares his snack with a homeless man, he begins a cycle of good will.

Featured in WOW Review Volume XII, Issue 4

In 2007, when a new edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary ― widely used in schools around the world ― was published, a sharp-eyed reader soon noticed that around forty common words concerning nature had been dropped. Apparently they were no longer being used enough by children to merit their place in the dictionary. The list of these “lost words” included acorn, adder, bluebell, dandelion, fern, heron, kingfisher, newt, otter, and willow. Among the words taking their place were attachment, blog, broadband, bullet-point, cut-and-paste, and voice-mail. The news of these substitutions ― the outdoor and natural being displaced by the indoor and virtual ― became seen by many as a powerful sign of the growing gulf between childhood and the natural world.

An alphabet book with fantastic and detailed pictures, bearing such labels as “Lazy lions lounging in the local library.

The jataka tales—stories of the Buddha’s past lives (in both human and animal form)—were first said to have been told by the Buddha himself 2,500 years ago. In print since the 5th century BCE, 550 jataka tales comprise part of the oldest Buddhist text, the Pali Canon. From this wealth of folklore, award-winning author and storyteller Rafe Martin has chosen ten tales that illustrate the ideals of the Buddhist paramitas, or “perfections” of character: giving, morality, forbearance, vitality, focused meditation, wisdom, compassionate skillful means, resolve, strength, and knowledge.Endless Path presents these ancient stories, usually reduced to children’s tales in the West, for adults, reconnecting modern seekers with the more imaginative roots of Buddhism. The jatakas help readers see their own lives, their failures and renewed efforts, in the same light as the challenges the Buddha faced—not as obstacles but as opportunities for developing character and self-understanding. Endless Path demonstrates the relevance of these tales to Buddhist lay practitioners today, as well as to those more broadly interested in Buddhist teaching and the ancient art of storytelling.

by Yuri Wellington, Ph.D.; Executive Director, Teach Cambodia, Inc.; Professor and Director, Cambodia International Pedagogical Institute

I recently read an article that described Cambodia’s literary traditions as “rising from the ashes.” In a country where nearly every author, teacher and intellectual was killed or driven out, literary traditions and genres are literally being recreated. Thus, the landscape of resources for children’ literature is very different from what we’ve come to expect in the USA, or in many other westernized countries. There are no “children’s” book authors or illustrators. In fact, most books for children are written and published by NGO’s, in an effort to publicize a particular civic or environmental concern. The stories are usually taken from traditional Cambodian folklore or actual accounts of historical events. Translated from the oral storytelling tradition, the text is often lengthy, with complex vocabulary and plot. While the illustrations are beautiful and intricate, these books definitely do not meet the criteria for “picture books.” Still, the stories and pictures never fail to hold the attention of even the youngest students.

One such book is Samnang and the Giant Catfish (Hogan, 2002?), which tells the story of the long migratory journey of the Mekong giant catfish and her encounters with a small boy along the way. I have to be honest, when I first heard about the giant catfish, I thought it was a joke! Folks, it’s no joke, and the plight of this huge, ugly creature is synonymous with the plight of all the people whose livelihoods are intricately tied to the Mekong and its tributaries. Many of these people –Cambodians, Laotians, Vietnamese, and Thai – are in danger of losing everything due to industrialization taking place all along the Mekong. It is a serious social, economic and environmental issue that impacts millions of people as well as other unique species such as the Irrawaddy Dolphins. The book links the importance of the fisheries in Cambodia to sustainability and clean waterways. A colorful field guide to native fish of Cambodia is also included.

When I taught multi-age classes in the early ‘90’s, everyone was fascinated by rain forests. Many of our cross-curricular “thematic units” focused on the rainforest – the ecosystems, the animals… Today, a major environmental around the world concern is global warming. One of the unique features of Southeast Asian society is the prevalence of subsistence farming and fishing alongside of cutting edge nanotechnology and incredibly rapid economic growth on a national level. Thus, exploration of culture like Cambodia using books such as those published by the various NGO’s I have discussed provide a unique opportunity to learn about distant cultures and global issues that directly impact us in the USA in the same moment. These books would make an excellent text set for such a unit.

The fact that these kinds of books are almost exclusively what is available suggests that perhaps a different genre of children’s literature is emerging from Cambodia, fueled by her history and her intellectual and literary rebirth in the 21st century. Hmmm…. I think that might be the focus of my final entry…. Aah, but I digress….

As I write this, Michael Lacapa comes to mind. I went to his online biography to investigate the connection. Help me out here, folks! I think the connection is in the deep connection to nature and the environment, and to the souls of his people that were the foundation of so much of his writing and illustration. It’s very different, and yet, it’s the same. In Cambodia, there is a saying that you see everywhere, “same same… but different.” Does anyone else see the connection? If so, write and tell me about it! Oops, more digression…

“So what are we supposed to do with the Khmer text?” WOW Stories recently featured an excellent article on Exploring Culture through Literature Written in Unfamiliar Languages . (Thomas and Short, 2011). Like the Korean writing described in the vignette, Khmer provides a wonderful opportunity to explore other lexicon. I still remember my own fourth grade teacher telling us about Egyptian hieroglyphics and challenging us to create our own written language and symbol. Due to the deep history of the writing that goes back over 8,000 years, an exploration of Khmer writing might also include a discussion about the history and development of written language.

In terms of exploring culture through unfamiliar language, we actually do the same ting in Siem Reap in our exploration of western culture through the use of English. Unlike central Siem Reap, Sambour village is quite remote, and most children and adults have never been anywhere else. They do not speak English, and are not familiar with it as the “town” folks are. They don’t see a lot of foreigners, and Sambour is not a destination on any tour. Thus, it is a curious circumstance that most of the books in the school library are bilingual. It is easy to understand when we consider the source of most children’s books… but curious, nevertheless….

Okay, bring it on home…

I’d like to close this blog with a more detailed description of three good sources for Cambodian Children’s literature that can be accessed from the USA.

Room to Read is a San Francisco-based NGO that publishes books in multiple languages for distribution in developing countries. As of 2010 RTR had published 96 Khmer children’s books, and a projected 25 additional titles were to be published in 2011. Every title is a collaboration by Khmer and western authors and illustrators. The stories and illustrations are culturally authentic, with high quality (i.e. grammatically and syntactically correct) Khmer and English text. Some of the books are fully bilingual (each page including both the English and Khmer text), while others are wholly in Khmer, with the English translation provided at the back of the book. At present RTR does not sell to individuals, but it is possible to purchase titles for libraries, and the books are also widely available through retail outlets in Cambodia.

Save Cambodian Wildlife is a Cambodia-based NGO that publishes to encourage protection of the environment and of Cambodian endangered animals. Environmental preservation is actually a critical issue throughout Southeast Asia, particularly in Cambodia where

All of the titles include “factoids” about the animals or environmental issues featured. These are great read-aloud books for grades K-3. Grades 4 and above could utilize these titles for guided reading, independent reading, and research about the environment. As a group, these books would make a great text set for study about environmental preservation.

SIPAR publishes bilingual and monolingual books in Khmer, Khmer-English, English, Japanese. Some titles are available in multiple languages. For example, the White Elephant’s Daughter is available in English, French, and Khmer. Interestingly, titles offered through SIPAR-Books.com are different from those offered through SIPAR.org. Some of the SIPAR-books.com titles use aastilted English cadence – obviously translated by a non-native speaker. The best quality titles are offered SIPAR’s label “White Elephant Books.” They do ship to USA (from France), and the cost is very reasonable. I have included the order form for White Elephant Books. (Please hyperlink to the attached document).

Now that we’ve talked a bit about what’s out there, what do you think? How might you incorporate Cambodian children’s literature into your classroom?

My next blog will focus on books published by quality vs. authenticity, and the difficulty of finding books FROM Cambodia that meet our literary standards. (or maybe I’ll address one of the other topics I touched on above…. Lacapa… emerging genres… you’ll just have to check back to find out!)

A parting treat for all of you: click here to watch some of our Sambour children exploring books during their recess time!

References

Hogan, Zeb (2002?). Samnang and the giant catfish. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Save Cambodian Wildlife.

Snaije, Olivia (2011). Cambodia, Where Literature is Being Reborn. Publishing Perspectives, 17 November, 2011. http://publishingperspectives.com/2011/11/cambodia-where-literature-is-being-reborn/

NOTE ABOUT REFERENCES: I struggle with appropriate annotation for books published in Cambodia. Most do not have a publication year, and there is no central clearinghouse or catalog that one can go to for citation information. There are also no ISBN or other tracking numbers. Thus, for books published in Cambodia, if there is no publication date listed then I used the date of the official government letter that appears in the introduction.

Websites:

Save Cambodian Wildlife. (publications for sale) http://www.cambodiaswildlife.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=74&Itemid=127

SIPAR – Soutien à l’Initiative Privée pour l’Aide à la Reconstruction des Pays du Sud-Est Asiatique: http://www.sipar.org/

SIPAR Books. http://www.sipar-books.com

Room to Read. http://www.roomtoread.org/

A collection of Robert Ingpen’s illustrations throughout his career.

All roads lead to kindness in this warm, uplifting celebration of generosity and love. In a colorful tree house, a rainbow of children determine the most important needs in our complex world, and following spreads present boys and girls happily helping others. Kids bring abundant food to the hungry; medicine and cheer to the sick; safe housing, education, and religious tolerance to all; and our planet is treated with care. Forgiveness and generosity are seen as essential, because kids know how to share, and they understand the power of love.

The Torah is the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, which Christians call the Old Testament. It tells the story of the beginning of the Jewish people and their relationship with God. From Adam and Eve to the first patriarch, Abraham, to Moses, who led his people to the promised land, the stories in the Torah have been studied and revered since it was first written down nearly 3,000 years ago.

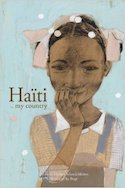

For several months, Quebec illustrator Roge prepared a series of portraits of Haitian children. Students of Camp Perrin wrote that accompanying poems, which create, with flowing consistency, Haiti My Country. These teenaged poets use the Haitian landscape as their easel. The nature that envelops them is quite clearly their main subject. While misery often storms through Haiti in the form of earthquakes, cyclones, or floods, these young men and women see their surrounding nature as assurance for a joyful, confident future.